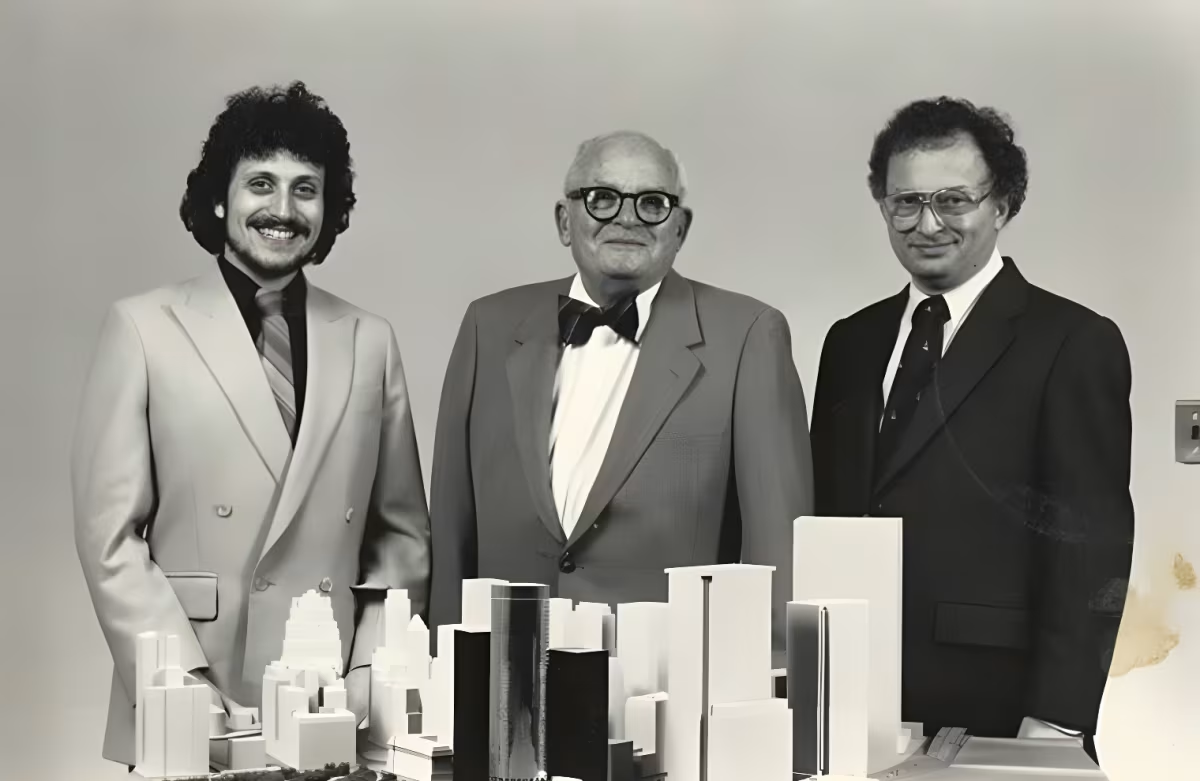

The MetLife Building is an International Style skyscraper designed between 1958 and 1959 by Emery Roth & Sons, with Richard Roth as lead architect, in association with Walter Gropius and Pietro Belluschi, and built between 1960 and 1963 in New York, NY.

MetLife Building is not the only name you might know this building by though. It is common for companies to want to attach their names to iconic buildings when they move in, or for the general public to come up with nicknames, and this one is no exception. The building has changed names several times over the years, and is also known as:

- Pan Am Building between 1963 and 1981.

- 200 Park Avenue between 1991 and 1992.

Its precise street address is 200 Park Avenue, New York, NY. You can also find it on the map here.

The MetLife Building has received multiple architecture awards for its architectural design since 1963. The following is a list of such prizes and awards:

- NYCxDESIGN Awards in 2022

- New York Design Awards Interior Desing in 2022

The building is built over two underground levels of train tracks that end at Grand Central Terminal. The lobby of the building also connects to the lobby of Grand Centra Station through a pedestrain walkway.

There used to be a heliport at the rooftop that was operational from 1960 until 1977, when it was closed after an accident.

The building has been restored 3 times over the years to ensure its conservation and adaptation to the pass of time. The main restoration works happened in 1987, 2002 and 2022.